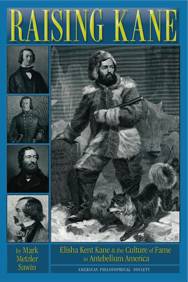

Raising Kane: Elisha Kent Kane and the Culture of Fame in Antebellum America

By

Mark Metzler Sawin

Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press, 2009, $35

Reviewed by Russell A. Potter

The meteoric rise to fame, and subsequent plunge into darkest obscurity of Elisha Kent Kane are unparalleled in American history. The transformation from a man whose name was on the lips of practically every American, news of whose return from the Arctic occupied the entire front page of the New York Times, to a man whose name evokes only half-hearted homonyms (Citizen Kane? Kwai Chang Caine?) is but one (though possibly the most dramatic) example of why Gore Vidal once dubbed us the “United States of Amnesia.”

Fortunately, the remedy for our public forgetfulness is at hand -- in this case, at least two remedies, Ken McGoogan's Race to the Polar Sea: The Heroic Adventures of Elisha Kent Kane, and Mark Sawin’s Raising Kane. McGoogan’s book, which is reviewed in this same issue, provides a rollicking good read and a suitably heroic figurehead, but those who are looking for deeper insight – both into Kane himself and why and how he rose to such extraordinary heights – would be far better served by Sawin’s book.

Kane, though forgotten by the public, has not quite spent the last century and a half in obscurity, at least not in the scholarly world. Jeanette Mirsky’s Elisha Kent Kane and the Seafaring Frontier (1954), George W. Corner’s definitive Dr. Kane of the Arctic Seas (1972), and more recently David Chapin’s somewhat wordily titled Margaret Fox, Elisha Kent Kane, and the Antebellum Culture of Curiosity (2004) have all tackled his career, or at least some aspect of it. Yet not until now has there been a biography which traces both the man and his public image from start to finish, drawing not only upon conventional historical resources, but upon the vast archive of newspapers, advertisements, handbills, and other ephemera through which that fame was constructed. Sawin’s book does all this, and does it with grace and equanimity.

In his undertaking, Sawin is the beneficiary of several significant developments since the time of Corner’s biography. The most significant of these is the discovery of the papers of Kane’s younger brother Thomas, now in the archives of the University of Utah (Thomas Kane had been a supporter of the Mormons’ religious freedom and a friend of Brigham Young’s). Tom and his older brother were very close throughout Elisha’s lifetime, and these letters provide many new insights into their and their family’s relationship. Secondly, the emergence of the Internet, including searchable newspapers and archives, has made available a tremendous amount of material that would otherwise, by the sheer labor of sifting through it, have been very difficult to use effectively. Among many other methods for spreading Elisha’s fame, his brother’s habit of clipping notices from small-town papers and forwarding them for republication in outlets such as the Herald Tribune and the New-York Times, can only fully be tracked through these means. Lastly, recent advances in our understanding of the mass media of the period – including not only newspapers but panoramas, lantern shows, public lectures, and the illustrated press – enable historians to give Kane’s career a fuller context, laying bare some of the machinery of fame hitherto hidden from sight.

These new resources, however, are only part of the reason for Raising Kane’s more vivid and well-documented account of Kane’s career. Sawin has marvelous eye for details, for plucking scarce diamonds out of the coal-pile of facts, that makes this book glisten. The items are small – a letter from a young and fancy-free Elisha to his brother asking for prophylactics (“gossamer envelopes”), an offer of a hot-air balloon for use on the second Grinnell expedition, the fact that James Hamilton actually lived in Kane’s home while working on the illustrations for Kane’s second book – but their collective impact is significant. Sawin’s book is founded upon exhaustive research in a tremendous variety of sources; he has cast his net wide, and not trusted merely to what previous fishers of facts have dredged up.

But most importantly, Sawin extends, strengthens, and makes definitive his earlier work on Kane's meteoric rise to prominence, giving the best picture we have of the machinery of fame in the mid-nineteenth century, and of how well Kane and his family managed the press and other media. We see Kane’s father and brother handling the ropes, pulling a few strings, and finally hoisting their social sails at just the right moment to catch the first “puffs” of public praise and hold them. It’s little wonder that Kane’s family was horrified at the prospect of his forming a connection with the spiritualist Margaret Fox, whose humble background, pay-per-view scéances, and overall naiveté in the world of social mores seemed to them utterly incompatible with the figure of “Dr. Kane” they had so carefully designed and defended.

To the actual voyages themselves, which in his day were the very essence of Kane’s fame, Sawin adds only modestly to our account, although his deft portrayal of Kane’s character makes his missteps during his expedition far more understandable. He we have a man both weak and strong, both extroverted and introverted, torn between a public which demanded perfection of their “Dr. Kane,” and his romantic inward self, who at times was perfectly willing to risk everything in the name of love. It may seem fortunate, in the end, that Kane died when he did; by doing so he avoided disappointing his adoring public, and in death redoubled the fame he had earned in life.

Given the concerted energy and gift for publicity of Kane’s family and friends, it’s little wonder that Hayes, or even the colorful Hall, could never manage quite the same claim upon the public eye, or retire with more than a few tatters of their reputations. It would not be until Peary, who through his wife was able to access a similar array of social cachet, strategic publicity, and public participation, that the Arctic would yield again its reluctant laurels, along with the often painful scrutiny such fame brings to those who must live with it.

Sawin’s book is not entirely without fault. There are, unfortunately, a number of typographical errors, more than there should be in a work of this kind. The problem is far from unique, and has been noted in these pages by several of our reviewers. Apparently, publishers generally have decided to skimp on the costs of copyediting in a supposed cost-cutting move, one which in fact saves little while losing much. Nevertheless, the book as a whole is thoughtfully designed, and richly illustrated with an impressive number of engravings, photographs, and handbills, many of which have never been published before.

Sawin's Kane, in the end, is not merely a Kane for our time -- it is a Kane for all times. By never losing track of the original, and best impulses upon which history is based -- curiosity, the awareness of chronological distance, and the desire to reach across this distance while remaining cognizant of its fundamental unreachability -- Sawin enables us to richly recall both the public figure of "Dr. Kane" and the private man Elisha from the lists of those whom time has, unjustly, forgot.