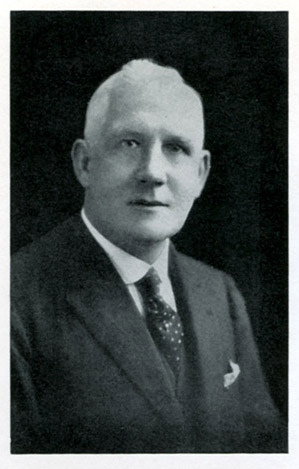

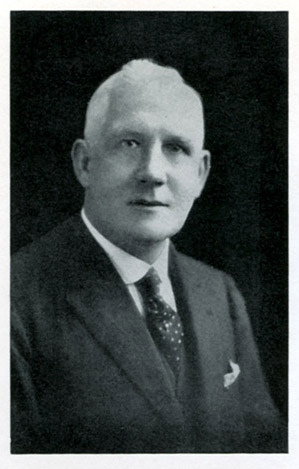

Chief Inspector Alfred Collins

Warrant # 81511

Joined the Metropolitan Police on August 10, 1896

Promoted to Sergeant, July 15 1904, and assigned to the C.I.D.

Promoted to Sergeant 2nd Class C.I.D. September 2, 1909

Promoted to Sergeant, 1st Class, C.I.D. September 13, 1913

Promoted to Detective Inspector, C.I.D., March 30, 1918

Promoted to Chief Inspector, C.I.D., July 7, 1925

Collins was a highly-regarded police detective who worked at the C.I.D., Scotland Yard, for more than thirty years in the early twentieth century. As a young detective sergeant, he discovered crucial evidence in the case of Louis Voisin, a French butcher who murdered his ex-mistress. The case began with the discovery of a mysterious parcel which turned out to contain a woman's torso. Scrawled on a scrap of paper found in the package were the words "Blodie Belgium"; by means of a laundry mark on a sheet which was wrapped around the body, police traced it to a woman who had, in the past, worked as Voisin's housemaid, but who had since gone missing. A search of the cellar at Voisin's house at 101 Charlotte Street, conducted by Collins, turned up a barrel of sawdust, inside which were found the unfortunate woman's head and hands. Voisin, interviewed by the police, was asked to write "Bloody Belgium" on a piece of paper, and his writing -- complete with the same misspelling -- was a key piece of evidence, as was a woman's earring found inside a towel in his kitchen.

Collins's reputation was challenged by the notorious Savidge case, in which Sir Leo Money was arrested for indecent behavior in Hyde Park with a young single woman. Sir Leo not only fought the charges, but demanded an apology from the police, which led to Collins questioning the woman involved, Miss Savidge, with an eye to vindicating police accounts. Collins was accused of badgering the witness, and faulted for not having a female police officer remain for the interview (Inspector Lilian Wyles). A Parliamentary inquiry ensued, at which the police were largely exonerated, and the Met changed its policy to mandate that women officers always be present when women were giving statements. Wyles and Collins remained on good terms after the inquiry was concluded, and he always carried, in his waistcoat pocket, a "lucky" mahogany bean which Inspector Wyles had given him during the hearings.

The inquiry, although it produced some worthy procedural reforms was, for Sir Leo Money, clearly a diversionary tactic. There is little question that he was arrested with good cause; in 1935 he was once again found in a compromising position in public with a woman; this time, he was duly convicted, and his reputation ruined. He spent his last years writing rambling political treatises and serving as an editor for the Encyclopedia Britannica.

By 1930, Collins had retired from the force, but remained active as a private investigator. In 1934, along with former Chief Constable Wensley, he played a role in the notorious Stavisky case, tracing some costly jewels which were pawned in London by an associate of Stavisky's.