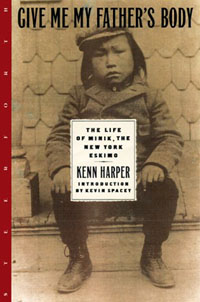

Give Me My Father's Body: The Story of Minik, the New York Eskimo

By Kenn Harper.

With a new introduction by Kevin Spacey

Steerforth Press, 300 pp., hardcover, $24.00

Reviewed by Russell A. Potter

Some stories have such intrinsic drama that, even in the barest outline, they are unforgettable. Such indeed is the story of Minik Wallace, a young Inuk brought with his father and four other members of his Northern Greenland band to the Museum of Natural History in New York by Robert Peary in 1897. Although not quite brought against their will, these six Inuit were only vaguely informed as to the purpose and meaning of their trip; some wanted to see strange places, others simply did not want to be parted from their relatives. Peary promised them all that they would be able to return. Yet on their arrival, it became clear that they, along with a meteorite that Peary thought of scientific value, were to be objects of study and exhibit, human zoo animals more or less, and that there were no plans for their care, let alone for their return. They were brought to a damp basement room, and as might have been foreseen, most of them soon came down with tuberculosis, against which they had little resistance. Studied, even as they were dying, by some of the most prominent anthropologists of the day, including Franz Boas (also remembered as Zora Neale Hurston's thesis advisor) and Alfred Kroeber ("discoverer" of Ishi and father of science-fiction novelist Ursula K. LeGuin), their last days were spent in agonizing pain without benefit of meaningful medical attention. Minik's father, Qisuk, was among the first to die, and the boy was inconsolable with grief. In this strange country, without the support of kinfolk, he pleaded for his father's body to receive proper burial, with traditional rites that only he (Minik) could administer. Yet already there were plans to preserve Qisuk's body for study -- study impossible were he to be buried. Out of embarrassment, or condescension, or simply convenience, the Museum's curatorial staff decided to stage a phony burial for Qisuk. They filled a coffin with stones, atop which a stuffed "body" was hidden under a cloth, and buried the box by lantern-light with Minik attending.

Eventually, all but one of the adult Inuit who had arrived with Minik

died, and the boy was left a complete orphan. Adopted by William

Wallace, the chief custodian of the Museum, he initially led a privileged

life at Wallace's estate in upstate New York. He attended school,

learned to read and write, and rode around on a bicycle provided by his

seemingly loving adopted parents. Qisuk's body was sent to Wallace's

own estate, where he operated a workshop for processing the skeletons of

biological specimens, and there it was de-fleshed and mounted on an armature.

In this form Qisuk's body was returned to the Museum for display as the

skeleton of a Polar Eskimo. Minik was yet unaware of this fact, and

his adoptive father kept it well hidden from him. Despite this, after

a space of a few years, the New York papers picked up on the irony of Minik's

father's bones being on deposit in the museum, and stories about it were

widely circulated. It was only a matter of time before Minik found out;

in Wallace's own words:

The poignancy of these words cuts across distances of time and culture, and the reader's identification with Minik's plight is intense. Scanning the horizon for villains, it is easy to pick out Peary, and with him Kroeber and Boas. But what of William Wallace himself? Or more: what of we ourselves, reading this text in our comfortable chairs? Living in a society which still reveres the memory of Peary, while it forgets the fate of Minik, are not we, too, culpable? And when we go to a museum today, might we not peer at bones whose anonymity masks an act of cultural theft and violation that, were the bones given a name, we would be ashamed to abet?"He was coming home from school with my son Willie one snowy afternoon, when he suddenly began to cry. 'My father is not in his grave,' he said, 'his bones are in the museum.'

"We questioned him and found out how he had learned the truth. But after that, he was never the same boy. He became morbid and restless. Often we would see him crying, and sometimes he would not speak for days.

"We did our best to cheer him up, but it was no use. His heart was broken. He had lost faith in the new people he had come among."

It is fortunate indeed that Minik's story has been recovered and told by as capable a hand as that of Kenn Harper. With a lesser writer, or one unacquainted with Inuit culture and language, the complex and contradictory threads of this tale might have devolved into a morality play, with Peary and his ilk meekly shouldering the blame we are ready to assign them, and Minik becoming merely an object of pity. Harper's gift is to tell Minik's story with all its strange twists and turns, including those which, at first glance, might seem to deflect or dilute our outrage. For instance, take William Wallace: while he certainly deceived Minik even as he became his adoptive father, he later greatly regretted his role in the sham burial, and did all that he could to ameliorate Minik's pain. Yet again, Wallace was no novice at deception; he in fact was caught billing improvements to his farm to the Museum, and it soon became clear to the Museum's directors that he had been doing so for years. Fired from his job, his life a shambles, his farm foreclosed, he too might be reduced to pity, but Harper keeps both his eyes clear, and gives us a Wallace that, in the end, we can see as destroyed by contradictions far larger than his own life could encompass.

Minik's own story, told with equal impartiality, nonetheless continues to be heartbreaking. His attempts to convince the Museum of Natural History to repatriate his father's bones fell on deaf ears; he benefitted little from the publicity attached to his case, and felt ill-at-ease in the society of his ostensible supporters. After eventually giving up on attempts to change the Museum's mind, he placed his trust in a campaign to get Peary to at least return him to his home. And, not out of shame but out of a desire to rid himself of this nuisance, Peary and his camp eventually made the arrangements for Minik to be returned to Greenland. Although they represented themselves as having sent him back "laden with gifts" (as the cliché goes), Harper has found clear evidence that on the contrary, Minik was returned to Greenland with little more than the clothes on his back.

The loss was immense. Minik had forgotten his language and much of his culture, and his life in Greenland was fraught with new difficulties. His people took him back, and taught him the skills he needed to know; he even became a fine hunter. But there was a strange, invisible line between him and the rest of the community; he became entangled in various tensions within the group, and was only 'in his element' when there were visitors -- Qaluunat -- with whom he could converse, and for whom he could serve as guide and translator. Both of these he did well, playing a key role in the otherwise misguided Crocker Land Expedition of 1913. This latest acquaintance with American visitors proved another turning point; Minik resolved to return to the United States, and did so in 1916.

Minik's final sojurn in the States was a brief one. After working at a series of miscellaneous jobs, he found work in a lumber camp in North Stratford, New Hampshire. His employer, Afton Hall, took him under his wing, and invited him to live with his family. It was however to be a brief idyll; Minik, along with many of Hall's family and workers, succumbed to the terrible influenza outbreak of 1918, dying despite the best medical attentions on October 29th. But Minik's story doesn't quite end there. Convinced that the remains of Qisuk and the three other adult Inuit who died with him should and still could be returned to Greenland, Kenn Harper worked his way through the resistance of the Museum of Natural History (which was reluctant to re-examine the case) and the red tape of two governments before finally being able, in 1993, to stand befrore a new grave in Qaanaaq in northern Greenland and witness the ceremony denied to Minik nearly a century earlier. It is worth noting that in this he had the co-operation and support of Wendy Wallace, William Wallace's great-granddaughter, as well as the wholehearted backing of the descendants of Minik's community of Polar Eskimos.

In a book as meticulous and thoughtful as this, the author can seem invisible at times, but Harper manages to say just what is needed, and when it's needed, to add to the difficult and poignant story he has so patiently uncovered. The haunting photographs of Minik, first as a baby, then as a sad-eyed boy in western dress with a bicycle, and finally as an adult back in Greenland, amplify and resonate with Harper's text. For years, Harper's book was available only by mail-order through a few shops in Canada, but Steerforth Press has remedied this situation with a handsome new hardcover edition. Award-winning actor Kevin Spacey has provided a thoughtful and evocative new preface, and word is that he has optioned the film rights for the book. It's a story that could indeed be admirably told via the medium of film; as Spacey himself notes:

When you get to the end of a great story there comes a moment of

silence, when the lights in the theater come up or when you turn the last

page in a book as good as this one, and you sit stunned.

One hopes, and expects, that Give Me My Father's Body will

have just such an effect on readers here as they turn the pages of this,

its first edition in the country that played host to the saddest episodes

in Minik's life.