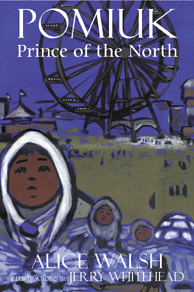

Pomiuk: Prince of the North, by Alice Walsh

Vancouver: Beach Holme Publishing, 2004

Reviewed by Kenn Harper

Beginning with the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Inuit (Eskimos) were exhibited at every major World’s Fair in the USA until 1909. In 1892, a group of about sixty Inuit were taken from Labrador to Chicago for exhibition. Some subsequently returned to Labrador; others remained in the USA. One of the Labrador Inuit taken in 1892 was a boy named Pomiuk, about eight years of age.

Canadian author Alice Walsh has written a children’s book about his life, or at least about parts of it. It’s a short book, 58 pages in length. Walsh notes that, although some of the people and events are fictionalized, the story is "based on the true-life adventures of an Inuit boy named Pomiuk."

The book fictionalizes Pomiuk and his tribe’s first encounter with white men, and his first view of the ship Everlina. Pomiuk’s adoptive father, Kupah, and his adoptive mother, Kootookatook, decide to go to America with the white men from the ship. As Kupah expresses his reason: "The white men promised us many things. In America we will never be hungry. And when we return we will have everything we need to make our life better." This is in fact an accurate summation of the reasons why promoters were able to entice large numbers of Inuit to give up their homes in Labrador on short notice and travel to an uncertain future in Chicago. Pomiuk, having heard the news, dreams of weasels, a sign of trouble to come, which convinces him that "something bad will happen to us in America." This image recurs throughout the story.

Aboard the ship en route to the port of Boston, in Walsh’s narrative, Kootookatook gives birth to a daughter, who is named Everlina after the ship. (In fact, this child was born after the party’s arrival in Chicago, on November 4, 1892.) Walsh also does not mention that Kupah’s and Kootookatook’s two other children, Sikepa (Pomiuk’s biological sister) and Tiguja, also went on the adventure to Chicago.

The story is told by Pomiuk in the first person. Through his eyes, Walsh describes life in the "White City," and all the wonders it holds for a young Inuit boy. Pomiuk is immensely popular at the fair and becomes known by the name Prince Pomiuk. He is expert with the dog whip, which he uses to flip coins tossed by tourists. For fifty cents, tourists can also ride a komatik — an Eskimo sled — but there is no snow and so the sled is drawn on a narrow railway, an idea which must have amused the Inuit hunters. Pomiuk endures a tragic accident at the fair. In a game of "kick" — an improvised soccer game — his leg is broken and improperly set. No longer the darling of the fairgoers, he has to crawl or be carried about and can only sit and watch as his friends continue to entertain the tourists with their whips. While in this sorry state, he meets a Mr. Martin, who befriends him. When the fair ends, he recounts, the Inuit leave the fair, having been defrauded by their promoter. "We leave with nothing!" Pomiuk says.

Ice conditions prevent the ship from taking them any farther than Bonne Bay, Newfoundland, where the postmaster, Mr. Roberts, lends them a house for the winter. The following spring, they return to northern Labrador. Pomiuk has become an invalid as a result of his damaged leg and the infection that has set in. Fortuitously, the missionary doctor, Wilfred Grenfell, visits his camp on his small hospital ship, Sir Donald, and takes the young boy away to his mission hospital. There Pomiuk endures an operation and his leg begins to heal. He is provided with a crutch. Since his return to Labrador he has exchanged letters with Mr. Martin, and these continue to reach him and cheer him in the hospital.

To this point Walsh’s story-line has held more-or-less true to the events of Pomiuk’s life. But her ending is troubling. It is a poorly contrived, stereotypically "happy" ending, one befitting a soap opera. At Christmas, Kupah and Kootookatook, the baby Everlina and Pomiuk’s older brother Kippinguk (who did not go to Chicago) come to visit him at the hospital. In the book’s final scene, the adoptive father Kupah extends his hand to Pomiuk and called him "eknerk" — the Eskimo word for son (properly "ernek" in Labrador dialect). Pomiuk is happy. "Never before has my heart known such joy," he says.

"Kupah called me eknerk, son. Someday he will return and take me home." In the "Author’s Note," which forms an epilogue, Walsh notes, "Unfortunately the boy’s leg never completely healed, and he spent the rest of his life on crutches."

This would be a wonderful and uplifting ending for young readers if it were remotely true. And the truth is a more compelling story than the one that Walsh has told. Pomiuk may have spent the rest of his life on crutches, but the rest of his life was remarkably short.

Pomiuk was the son of Kajuatsiak (Kaiouchouak), a powerful leader in the Nachvak area of northern Labrador, and his wife Aniortama (Anniortama). But when Kajuatsiak was killed by Kolliligak (Kalleligah), his mother remarried and gave her three children away to be raised by others. Pomiuk and his sister Sikepa went to live with Kupa’s (Kupah’s) family, while his brother Kippinguk went to the family of Kupa’s older brother, Tuglavina. In 1892, Kupa and his wife, Kuttukittok (Kootookatook), their daughter Tiguja and the two adopted children, Pomiuk and Sikepa, went to Chicago to be exhibited as part of the Esquimaux Village there. While on exhibition, Pomiuk broke his hip, probably through the roughness of Kupa himself in one of their exhibitions, and not through the roughhouse antics of his innocent and fictitious playmate, Mukpa, of Walsh’s story.

Bilked by unscrupulous promoters, the family returned to Labrador after the fair. In the summer of 1895, Grenfell found the boy living as an invalid with Kupa’s family near Nachvak, "a naked boy of about eleven years, an old reindeer skin thrown over him… and his face drawn with pain and neglect." (Forbush 76) His thigh was broken and diseased. Grenfell took Pomiuk to his seasonal hospital at Indian Harbour at the mouth of Hamilton Inlet (not Red Bay as Walsh says), then transferred him to Burnt Wood Cottage Hospital, farther up the inlet near Rigolet. The following May a Moravian missionary baptized him with the Christian name, Gabriel. That fall he was transferred to Grenfell’s hospital at Battle Harbour.

The mysterious Mr. Martin of Walsh’s narrative maintained a correspondence with Pomiuk and also with Grenfell. In fact he was Charles Martin, children’s editor of a religious paper, The Congregationalist, and himself a former missionary. He and his readers contributed financially to Pomiuk’s upkeep.

Pomiuk was finally fitted with crutches in the summer of 1897 while in the care of Dr. Wilway at Battle Harbour. But the happy ending that Walsh has created never happened. There was no joyful reunion with his adoptive parents and his sister Everlina - in fact, the baby Everlina had died shortly after the family’s return to Nachvak — although Mr. and Mrs. Ford and their boys, the trading family from Nachvak, visited him in September. A few days later, on September 29, 1897, Pomiuk succumbed to the disease that had debilitated his young body since the infection that accompanied his broken hip. He died in the hospital that had become his home. Dr. Aspland buried him in the churchyard a few days later.

Charles Martin and his readers wished to provide a lasting memorial to the Eskimo boy who had become their friend through the pages of The Congregationalist. They arranged to have his bed named the Gabriel Pomiuk Memorial Cot, and they continued to provide funds to the hospital.

In 1903 William Forbush published a biography of this unfortunate Eskimo boy under the title, "Pomiuk, A Prince of Labrador," a rare book today. It is a more complete telling of Pomiuk’s sad saga than that of Alice Walsh, and it does not avoid presenting the unfortunate conclusion to the story. The Periodical Accounts of the Moravian Brethren also shed some light on the circumstances of Pomiuk’s sad life.

Young readers should not be spared the truth of this boy’s regrettable adventure. Walsh’s book sanitizes his life and avoids the unpleasantness of his sad end. Fiction or not, this is not the story that needed to be told. The illustrations by Jerry Whitehead, a Cree from Saskatchewan, are stark in their simplicity. The cover, showing the plaintive face of Pomiuk overshadowed by the Ferris wheel of the fairgrounds, is especially compelling.