Rhode Island's Revolution

The roots of revolution run deep in Rhode Island, in some ways dating to the original settlement by Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson and other like-minded dissenters in the 1630s. Throughout the 18th century, many Rhode Islanders, especially those engaged in shipping, challenged British authority through tax evasion and smuggling, and often openly disregarded the law.

Rhode Island’s legislature sent Stephen Hopkins to the Albany Congress in 1754. The congress was called to discuss how to improve relations with the Iroquois and other Indian nations, and to consider a common defense against France. But it also was the first meeting of colonial representatives and it served as a precursor to the later Stamp Act Congress of 1765 and the First Continental Congress in 1774. Delegates debated Benjamin Franklin’s Albany Plan of Union, which called for a union of eleven colonies, represented in a new legislature that would have responsibility for relations with Indians. Hopkins and the other delegates adopted the plan, but the colonies’ legislatures rejected it.

Instead the colonies remained politically disunited during the ensuing French and Indian War (the Seven Years War), though wartime service in distinct colonial units, separate from British units, helped to develop a sense of American identity during that conflict. Simeon Thayer of Providence fought in Roger’s Rangers during the French and Indian War, and later would lead local militias in the revolution.

Unity came to the colonies when victorious Britain, in order to pay for the war and for some of the expense of maintaining its larger North American empire, introduced new and higher taxes on the colonists, most notably through the Revenue Act (1764), Stamp Act (1765), Townshend Acts (1767), and Tea Act (1773). Each of these measures significantly impacted life in the colony.

In October 1762, William, Sarah, and Katherine Goddard started the first newspaper in Providence, the Gazette and Country Journal. Through this medium, and through the publication of several pamphlets, including Stephen Hopkins’ famous Rights of the Colonies Examined in 1764, the Goddards kept Rhode Islanders informed of developments and opinion during the crucial decade of the 1760s. Men and women responded by joining organizations like the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty, which Freelove Fenner Jenckes founded in Providence.

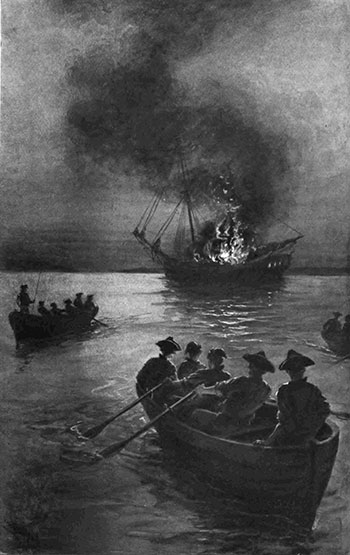

The Violent Turn: The Burning of the Gaspée

The colony was an active participant in the opposition to the Stamp Act in particular, but the most notable revolutionary event that occurred in Rhode

Island was the Gaspée Incident of July 1772, the result of nearly a decade of dispute between the

British government and colonials who increasingly felt they were losing their liberties to a tyrannical and foreign power. With so many prominent Rhode

Islanders engaged in trade, British efforts in the 1760s to enforce trade laws and collect customs duties were met with complaints, flippancy, and

resistance.

When the government of King George III ordered the HMS Gaspée to patrol the Narragansett Bay in order to halt rampant illegal smuggling, Rhode Island ship captains did their best to avoid detection. One of these men, Captain Benjamin Lindsay of the packet ship Hannah, lured the pursuing Gaspée into the shallows off Namquid Point (now Gaspée Point), where it ran aground on a sandbar. Seeing the British vessel stuck, Captain Lindsay went on to Providence, where he informed John Brown of the situation. As a leading shipping merchant (and smuggler), Brown issued a call for interested parties to meet at James Sabin’s Tavern to plan the Gaspée’s destruction. Among those who boarded the eight boats and rowed quietly out to the ship were John Burroughs Hopkins, who captained one of the long boats and was the son of Esek Hopkins, the brother of Stephen Hopkins. Two other long boat captains that night were Joseph Tillinghast and Christopher Sheldon. Among the other raiders were Simeon Olney, Paul Allen, Abiel Brown, Pardon Sheldon, and Joseph Brown, the brother of John Brown.

After boarding, eighteen-year-old Joseph Bucklin V apparently shot the officer in command of the Gaspée, Lieutenant William Dudingston, who had

come on deck to confront them, and wounded him in the groin. Another young Providence man, twenty one-year-old John Mawney, administered medical attention

and removed part or the entirety of the bullet. Dudingston survived and he and his crew were removed to Pawtuxet Village. The Gaspée was set

ablaze and burned down to the waterline before its powder room exploded.

Growing Discontent

No one would ever come forward with information about the incident, despite the £1000 reward offered by the king. The British government considered the affair to be treason, and perhaps an act of war, but authorities in Rhode Island, led by Chief Justice Stephen Hopkins, refused to cooperate in the investigation. The events caused a major stir in the colonies and led to inter-colonial discussions of how to respond to the incensed British authorities between key revolutionary figures like Hopkins, John Adams and Samuel Adams.

In 1774 the colonies sent delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Stephen Hopkins and his political rival in Newport, Samuel Ward, represented the people of Rhode Island. This group organized the formal boycott of British goods as a protest against the Coercive Acts. Hopkins also served in the Second Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence.

The War for Independence

At least 300 Rhode Islander’s buried in the North Burial Ground helped win independence. During the years 1775 through 1781 North Burial Ground residents fought battles on land and sea, tended the wounded, and endured imprisonment. Many more revolutionary veterans are interred in North Burial Ground than are identified in the narrative that follows, but those we chose are representative of the veterans who fought in the War of Independence.

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Siege of Boston began. The Continental Congress asked each colony to contribute “Continental Line” Regiments to a continental army commanded by Washington. Charles Haskell, an African American, served as a soldier of the Massachusetts Line within the Continental Army. Simeon Thayer of Providence raised a local company that marched to Boston and took their place in the Rhode Island Line. Silvanus Martin, living in Windsor, Connecticut at the time, marched with the Connecticut forces that became part of Washington’s army at Boston. Martin left a terse diary of the events at Bunker Hill in June 1775.

There was a great deal of fluidity within the military organization of the American forces. Regiments and local and county companies were often combined, merged or otherwise blended as combat, illness and expired enlistments took their toll. Some state and local units remained detached. William Barton served in both continental line regiments and state militias. In July 1777, Barton led nearly forty Rhode Island militia and line regiment soldiers on a raid that captured British General Richard Prescott, the British forces commander in Rhode Island, who, ignominiously, was captured twice by American forces during the Revolutionary War.

The Rhode Island Continental Line units came to include the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment had two incarnations. Originally formed from units that marched to Boston as “Varnum’s Regiment” in May 1775, by June 1775 it was re-designated the 9th Rhode Island Continental, with James Mitchell Varnum in command. In 1777 Washington’s army was re-organized again and the 9th was designated the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, commanded by Colonel Christopher Green until the regiment was merged with the 2nd.

The 2nd Rhode Island Regiment was formed in 1775 from the Providence County militia under command of Daniel Hitchcock. In January 1776 it was designated the 11th Continental Regiment. In September 1776 the 11th was re-designated the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment and when Hitchcock died in January 1777, Colonel Israel Angell became the 2nd Rhode Island’s commander.

Due to losses suffered during 1776 and 1777, while at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78 the 1st R.I. Regiment was merged into the 2nd R.I. Regiment. The officers of the 1st were dispatched to Rhode Island to recruit more soldiers for the regiment. In 1778 Governor Nicholas Cooke informed the Continental Congress that the Rhode Island General Assembly had authorized the 1st Rhode Island to recruit slaves into its ranks. The 1st Rhode Island became known as the “Black” Regiment. Colonel Christopher Greene remained in command. Later in the war, when Greene was killed in 1781 at Croton River, New York, Jeremiah Olney replaced him as commanding officer.

The Battle of Rhode Island

By the end of the war the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island line regiments had participated in battles from Bunker Hill to Yorktown. Units of both participated in the Battle of Rhode Island (August 8 to August 30, 1778), which was fought in Newport, Portsmouth and Tiverton and was the most significant local clash of the Revolution. John Angell, Charles Laurens Bogman, Stephen Harris, Samuel Healy, Aaron Man, Henry Randall, Daniel Smith, Jabez Whipple, Ceesar Wheaton are among those in North Burial Ground clearly identified as rank and file soldiers in the “expedition to Rhode Island.” Washington placed Major General John Sullivan in command, his Deputy Adjutant General was Colonel William Peck and Assistant Quartermaster General was Dexter Brown. Israel Angell commanded the combined elements of the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments with Christopher Greene. The “Black” 1st Rhode Island Regiment played a pivotal role in the battle. While the battle itself is considered to be inconclusive to the outcome of the Revolution, not long after it, British forces left Newport.

The War at Sea

Rhode Islander’s fought at sea as well. Charles Allen, Jeremiah Brown, Joseph Cooke, Thomas Jackson, Sylvanus Jenckes, William Rodman, Christopher and Israel Sheldon were crew and captains on the array of brigs, sloops and schooners acting as privateers or as vessels making up the fledgling continental navy, commanded for a time by Esek Hopkins.

POWs

Some patriots such as David Arnold, Allen Brown, Oliver Jillson, Henry Harris Tillinghast were taken as prisoners, sometimes exchanged or died in British prison ships such as the notorious Jersey in Wallabout Bay in New York’s East River, which was the fate of David Dunwell.

Many thousands of other American soldiers during the Revolution suffered the same fate as Dunwell. A Prison Ship Martyrs Monument and crypt, designed by McKim, Mead and White, the same architectural firm that designed the Rhode Island State House, was dedicated in 1908 in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park, a Frederick Law Olmstead designed public space.

Medical & Humanitarian

A few of the medical personnel in the ranks are interred in North Burial Ground: Stephen Gano was a naval surgeon, Joseph Hewes was a surgeon’s mate early in the conflict and became a regimental surgeon later, and Olney Winsor was a commissary and later a surveyor general of military hospitals.

Rhode Island Quakers such as Moses Brown faced a difficult choice during the war. As Quakers they were pacifists and most would not take up arms under any circumstance. Instead many Quakers acted as humanitarians, for example taking food and supplies across British lines to those in need during the Siege of Boston. However, other Rhode Island Quakers, such as General Nathanael Greene, decided the political situation trumped their faith’s pacifism and joined the battle.

The Road to Yorktown

It might be said that the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown began in Rhode Island because in June 1781 French forces under the command of Jean-Baptist Donatien de Vimeur, le comte de Rochambeau began to arrive in Providence and encamped throughout the town in preparation for their pivotal march to Virginia. On June 16, 1781 there was a grand review of the French Army before it left two days later. After Yorktown, the French Army returned to Providence and encamped near the home of Jeremiah Dexter, which still stands today at the corner of North Main Street and Rochambeau Avenue, across from an entrance to the North Burial Ground.

In North Burial Ground there is a granite monument to commemorate the graves of the more than one hundred French soldiers who died while in Rhode Island during the American Revolution. It was presented on July 4, 1882 by the Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Two original members of the Rhode Island Sons of the American Revolution are buried in North Burial Ground: Esek Arnold Jillson and Nathaniel Greene Totten.

There are hundreds more Revolutionary veterans buried in North Burial Ground—mostly forgotten men such as Samuel McClellan and Fenner Angell. Each has their own story. If you have an interest in finding information about additional veterans of the American Revolution, visit http://www.rihistoriccemeteries.org/ (PV001 is the code for North Burial Ground). If you wish to add someone to our revolutionary era tour please contact us at northburialground@gmail.com.