The Voice of Legendary Alumna Rose Butler Browne

- News & Events

- News

- The Voice of Legendary Alumna Rose Butler Browne

An educator, activist and the first Black woman awarded a doctorate by Harvard, Browne remains a legend at Rhode Island College. This is a 1969 interview she gave to a reporter for the RIC Alumni Magazine.

Fifty years ago this June, Rose Butler graduated from Rhode Island College (then Rhode Island Normal School ) and, with 127 classmates, left the confines of the Promenade Street campus in downtown Providence for a career in teaching.

On commencement day, 1919, she stood out in the auditorium as the only Negro receiving a degree. Today she stands out in Durham, N.C., and in many other cities throughout the country as a symbol of dignity and achievement.

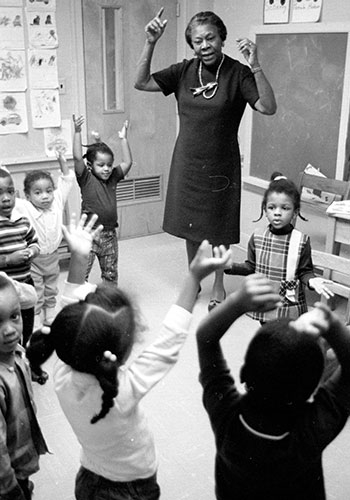

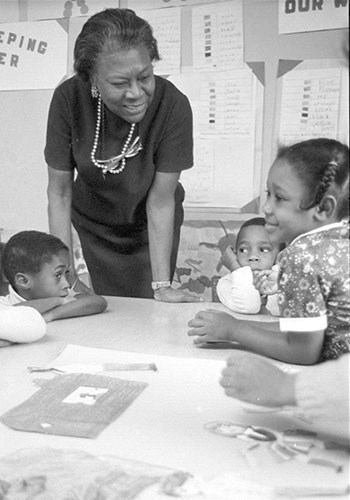

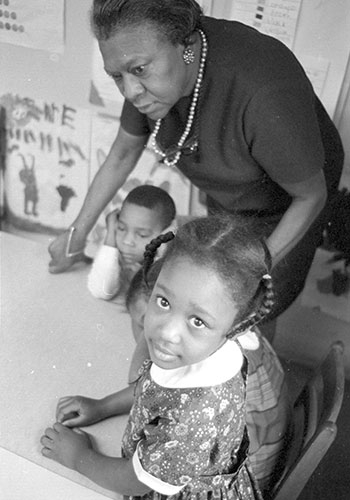

Although officially retired since 1963 as a professor of education at North Carolina College, Dr. Rose Butler Browne shows no sign of slackening her pace. Her age betrayed only by the streaks of grey in her hair and the black-rimmed reading glasses that dangle on a chain from her neck, Mrs. Browne directs the Happy Hours Child Care Center at the Mount Vernon Baptist Church in Durham, where her husband, The Rev. Emmett T. Browne, is pastor.

Each morning at 8 a.m., the church, in an urban renewal area less than a half mile from North Carolina College, welcomes 60 children of pre-school age who come for the day. With the assistance of several women from the parish, Mrs. Browne has set up a program of learning, similar to Head Start, to prepare the children for public schools.

'“The opportunity for upward mobility is the single most essential factor in guaranteeing social justice,” she says. “And the way Negroes can assure themselves of this is through education.”

The challenge and pursuit of excellence has been a life-long quest for the soft-spoken woman who spent her youth in Newport, R.I.

The third of seven children in a family of modest income, Rose Browne credits her father with imparting to her the philosophy by which she has lived and taught. “Always set your sights high,” he advised, but Rose learned early that the paths to that goal were not always smooth.

While Dr. Browne recalls pleasant associations at the Normal School and knew the comfort of social acceptance by her classmates, she also remembers some of her friends’ parents were not reconciled to the thought of having a Negro in their homes.

After completing the two-and-a-half year course at the Normal School, Rose became the first graduate to take advantage of the new, cooperative program with Rhode Island State College (now URI) that allowed her to complete the bachelor's degree program.

With her degree in hand, Rose Butler joined the faculty of Virginia State College in Petersburg in what was to be the beginning of a 47-year career in teaching at Negro colleges in the South.

The first 17 years were spent at the Virginia college, with time set aside for earning a master's degree in educational psychology from Rhode Island College in 1929 and a doctorate in the same field from Harvard in 1939. (Her doctorate was the first ever awarded to a Negro woman by Harvard.) In 1950 Rhode Island College awarded Dr. Browne an honorary doctor of education degree.

While at Virginia State, Rose met the man she was to marry. The Rev. Emmett T. Browne, a minister, was a student in one of her in-service classes for elementary education teachers and was serving as principal of a local school.

After Virginia State, Mrs. Browne spent the next 18 years in West Virginia, first at the State College Institute for a year, then at Bluefield State for l 7 years.

While at Bluefield, Mrs. Browne made a dramatic move to point out the unequal treatment being given Negroes in teaching at that time. In addition to her classroom duties, she was also serving as placement director for the college which was one of the major sources of Negro teachers for Negro schools.

The state of West Virginia had a hiring practice of recruiting white teachers for white schools and equipping those schools first, and, with whatever remained of the state allocated funds, hiring Negro teachers and equipping their schools.

“What resulted,” Mrs. Browne says, “was that Negro education became an afterthought on the part of the board of education and consequently Negro teachers were paid correspondingly lower salaries and the facilities in which to teach were substantially poorer than in the white schools.”

Seeing that this was separate but hardly equal education Mrs. Browne reacted one year by refusing to channel her graduates into teaching positions in the state. Since Bluefield was a state college, this caused some consternation within the board of education. The president of the college was called and he, in turn, went to Rose Browne.

Mrs. Browne was subsequently relieved of her placement duties, but by drawing attention to the second-class treatment of Negro education graduates and their schools in the state, she forced the issue which resulted, gradually, in more equitable salaries and facilities for Negro teachers and, consequently, a better educational environment for Negro pupils.

When her husband’s parish was transferred to Durham, N.C., Mrs. Browne joined the faculty at North Carolina College. Here, in addition to her classroom work, she served as chair of the education department.

Reflecting on the years at NCC, she points with pride to the master of education program she initiated to help graduates pass the national teachers examinations, at the time, a convenient tool to stop Negroes from gaining equal job opportunities.

Rose Browne still has close ties to NCC despite her official retirement, teaching an occasional education course. Although the day-to-day trek to the nearby campus has ended, Rose’s dedication to education and dignity for the Negro has not abated in the least. In addition to the daycare center and part-time teaching, she is a consultant to the Durham school department, a member of the North Carolina Governor’s Commission on the Mentally Retarded, a member of the state day-care licensing board, and secretary-treasurer of the Mt. Vernon Baptist Church credit union.

It was lunchtime, and as the children filed past her small office in route to the kitchen and cafeteria that had been installed in the church basement, Dr. Rose Butler Browne paused to sum up her feelings on the past – and on the future.

“I’m not a compromiser,” she said. “I have never reconciled myself to a substandard effort or below par achievement. And, I doubt I ever will.”

This article, by reporter Philip Johnson, has been condensed and reprinted from “The Review: Rhode Island College Alumni Magazine,” Spring 1969.