The In-Between World – The Art of Alumna Magda Léon

- News & Events

- News

- The In-Between World – The Art of Alumna Magda Léon

“In America, we talk about the American Dream, but the American Dream is very expensive for immigrants. There’s a personal price we pay to come here,” says Léon.

“My parents were running away from the civil war in Guatemala when they met in Rhode Island. That’s where they married. When my mother was seven months pregnant with me, they flew back to Guatemala so I could be born in their homeland. Ever since, I’ve been back and forth between Guatemala and the United States. I would go to Guatemala in the summers or for a year and once for five years. Children of immigrants live between worlds.”

These are the words of 44-year-old Magda Léon. Five years ago, this artist, wife and mother of four enrolled in RIC’s art program, graduating in 2021 with a concentration in printmaking.

In retracing her life as an artist, she recalls discovering her life purpose as a little girl drawing on the floor of her grandmother’s kitchen in Guatemala. “I was using a crayon to draw a heart,” she says. “I kept trying and trying.” When she was finally able to create what she felt inside, she made the life-changing discovery that she was indeed an artist. “After that, I was drawing on everything – passports, walls, everything.”

The theme of much of Léon’s art is on the immigrant experience, particularly the experience of children of immigrants. Each piece she creates is rich with ethos – character, atmosphere and mood.

In her senior year at RIC, Léon was given a public stage for her work. The owners of Aguardente, Fox Point’s newest restaurant, commissioned her to paint a series of four murals depicting the immigrant experience.

“The owners and I have been longtime friends,” she says. “My husband and I have traveled with them, and we are all lovers of culture, food and art. But I’ve never painted a mural before. To take on this job was a heavy responsibility, yet a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They put a lot of trust in me. They gave me a huge platform for my art. It has meant the world to me.”

The artist also designed the restaurant’s logo and menu (a blend of Portuguese and Guatemalan cuisine), and because of her cooking prowess, Léon was asked to provide recipes for all seven of the Guatemalan dishes.

Aguardente’s owners are immigrants of mainland Portugal and the chef an immigrant from the Azores. Ultimately, their website reads, Aguardente is “a place to celebrate our collective upbringings in Portugal, Guatemala and the Azores,” “a place where food, spirits and art tell the stories of home.”

Léon completed her commission in December 2021.

Léon says her art was inspired by the work of Mexican political cartoonist José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), who published his prints in local newspapers. “His work informed the Mexican people, even the illiterate, about what was going on politically,” she says. “I think printmaking is a medium that speaks to the people.”

Léon does a lot of relief printing. Relief printing involves carving an image into a block of material, applying ink to the surface of the block and then pressing the block onto paper to produce a print of the image. The most common forms of relief printing are woodcut (prints made using a block of wood), linocut (prints made using a sheet of linoleum) and wood engraving.

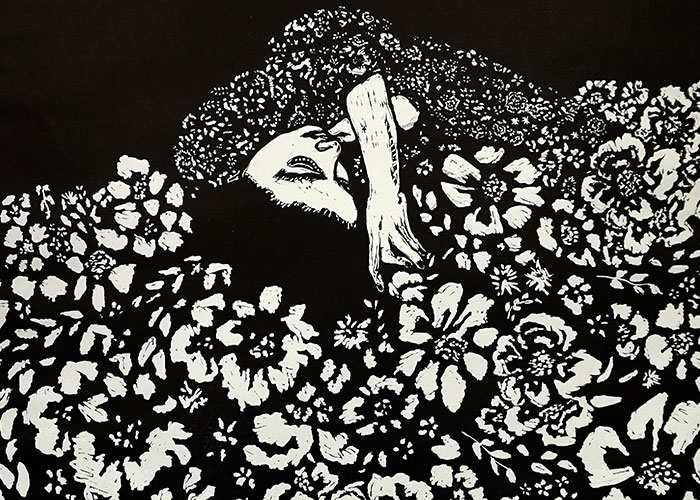

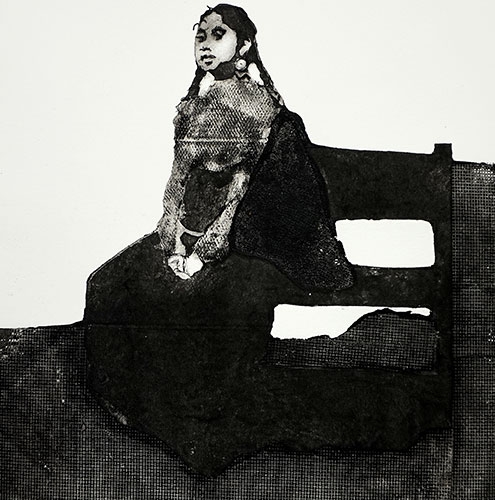

In a series of linocuts titled “Flowers Among Many,” Léon depicts Guatemalan women in what she calls “resting poses.”

In “I’m Your Crown,” a woman wears a dress fully adorned with flowers along with a crown of flowers.

“She’s resting in her own story,” Leon explains. “She’s resting in her own beauty. She looks straight at you, with pride, as if to say, ‘This is who I am and I’m resting in it.’”

Though Léon’s art reflects the reality of life in Guatemala, she recognizes that she can never completely fit in there. “To Guatemalans, I am someone who left their culture, I am la Americana. Yet I also don’t fully fit into American culture, with English as my second language.”

“Children of immigrants find themselves in this in-between space,” she says, “connected yet disconnected at the same time. The only space where I feel completely at home is with other children of immigrants. It doesn’t matter what country we come from. We share a commonality. We dwell in this in-between world.”

“That in-between state has helped me appreciate and feel the pain of families who are torn apart,” she says. “Someone in the family had to leave to provide for the family. Husbands had to leave wives and marriages were never the same. Parents had to leave children. There’s pain and hurt that isn’t expressed or talked about. There’s also the guilt we feel knowing our parents sacrificed so much, struggled to survive in a violent country, a violent war.”

“In America, we talk about the American Dream, but the American Dream is very expensive for immigrants,” she says. “It’s not free. It’s not easy. There’s a personal price we pay to come here, but we know we did it for the survival of our families.”

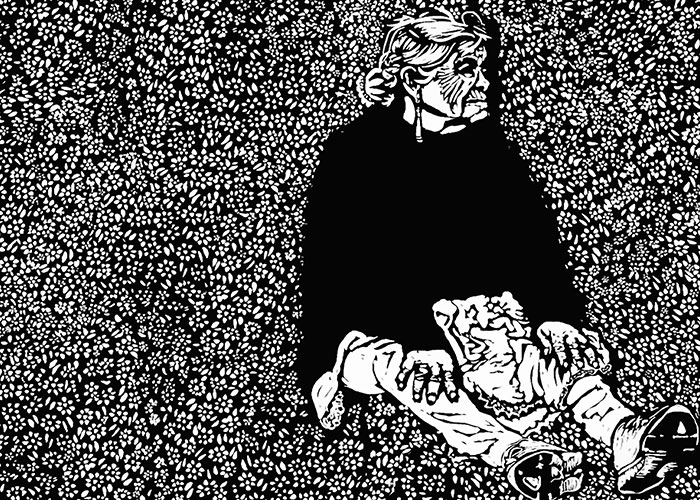

In another linocut titled “Golden Banana,” Léon likens the exportation of bananas to the exportation of men.

“Guatemala is known for its bananas,” she explains. “If you read the tag on a banana at the supermarket, most likely it came from Guatemala. We export bananas in the same way we export men. The man in this linocut is one of the ‘golden bananas’ being exported to America.”

In fact America has always been a nation of immigrants, spanning every race, religion, ethnicity and sexual identity. Yet, historically, there has always been antagonism toward new arrivals. On the one hand, the Statue of Liberty proclaims that anyone can be an American:

“Give me your tired, your poor; your huddled masses yearning to breathe free; the wretched refuse of your teeming shore; send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me.”

Yet on the other hand, we stereotype and treat anyone who lands on these shores as something other than American. The Statue of Liberty’s promise and the positive spirit of the American Dream was somehow lost.

In a poem written by Léon to accompany her series of murals, we hear the pain of leaving a loved one behind:

This is an undocumented love story.

It starts with a dream, but ends in contradiction.

Profound are the gasps that come from my soul when I remember your face, surrounded by the dawn.

Goodbye. I’ll see you soon, if nothing changes. For life sometimes takes us down anger-filled paths.

Goodbye. I’ll see you soon.

If life is wise, then this blessed and long distance will not become the end of us.

After completing her commission last month, Léon began applying to graduate schools to earn a master’s degree in printmaking. “I’m interested in transferring my prints to fabric. I’d like to make indigenous clothing with patterns or images that tell the story of the immigrant experience,” she says.

She works in the wee hours of the night, when the house is sleeping. Each new piece begins with an emotion rather than a specific form or image. That emotion moves through her fingers, carving out the story of her people.