Creating a Forum for Difficult Discussions in the Classroom

- News & Events

- News

- Creating a Forum for Difficult Discussions in the Classroom

We want our students to feel free to discuss their thoughts on controversial social and political issues in the classroom.

“Some of the most important issues of our time – such as social justice, racism and institutional inequities – may sometimes seem impossible to talk about except with people with whom we already know we agree. Yet if we are to progress as a society, we must find ways to have these talks instead of becoming increasingly isolated within small groups of like-minded people.”

These are the sentiments of Professor of Communication Valerie Endress, director of the American Democracy Project; Professor of English Maureen Reddy; and Professor of Psychology Christine Marco, director of the Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning.

In 2018 Endress sought to bring difficult conversations training to RIC as part of the American Democracy Project. She partnered with former Unity Center Director Antoinette Gomes and together they invited Essential Partners to provide the training.

Essential Partners is a nonprofit organization that has been training colleges, civic groups, faith communities and workplaces for over 30 years on how to facilitate dialogue across differences, mediate conflict and manage interpersonal as well as intergroup challenges in their lives, communities and workplaces.

Following Gomes’ retirement in 2018, Endress asked Reddy and Marco to join the project. Delayed three years by the COVID-19 pandemic, the trainings finally came to fruition on May 16 and 17, with 20 faculty members and 20 students in attendance.

Asked why social and political discussions are so difficult to have in today’s classrooms, Reddy replies, “When you see how polarized these issues have become, how people are on one side or the other and aren’t listening to each other but shouting at each other, you can understand why faculty and students are avoiding these discussions in the classroom.”

“Faculty are afraid to address these topics out of fear that they’ll mishandle them, and students are afraid to express their beliefs in class or disagree with their professor out of fear that they’ll be punished for it with a bad grade,” she says. “Though faculty are experts in their disciplinary areas, they’re not necessarily experts on how to facilitate conversations around controversial topics.”

“Yet a dangerous default is to say and do nothing,” notes Marco.

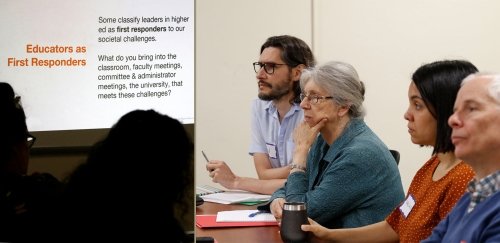

For this professional development training, Essential Partners sent four facilitators to train RIC students and faculty. They discussed the Dialogic Classroom model, where participants create agreed-upon ground rules for structured discussions. They discussed listening to understand, asking questions for clarification rather than to convince the other person that they’re wrong and learning to embrace contradictory perspectives.

“We want our students to be able to sort through the cacophony of perspectives out there,” Endress says. “That’s what college is for – to test out those things that your parents told you, that your community told you, that your friends told you. However, that process of testing out absolutely depends on verifiable facts.”

“For example, I had a student who wanted to do her speech on the idea that the earth is actually flat and not round. She said, ‘There’s evidence to show that the earth is flat.’ And I replied, ‘No, there’s no evidence to that effect. Feel free to research it.’ She replies, ‘You can’t tell me I can’t do this speech. I have a right to my own opinion.’ And she walked away very angry and dropped the class. We, as faculty, have to know how to respond to situations like this,” particularly when “alternative facts” are something students are bringing to the discussion table.

She underscores the importance of critical thinking and fact-checking when having difficult discussions.

Ultimately, faculty and students must learn to shift away from the typical way of discussing difficult or polarizing topics and create a supportive forum for discussion by adopting a different pattern of speaking, listening and inquiring.

It is hoped that faculty who have gone through the training will later become facilitators, teaching what they’ve learned to other faculty and that students will become facilitators whom professors can call on to assist with in-class discussions. Faculty know that a peer may be able to reach another peer in a way that a professor can’t.

“We know we can’t tamp down controversy – nor should we,” Endress says. “It’s part of a liberal arts education to engage in the issues of our time. Ideally, we want to create an engaged campus, where Rhode Island College is known as a place where controversial ideas are discussed and challenges are worked through.”