Making campus a welcoming space for all is as much about removing obstacles as it is about providing resources.

“To make a campus truly accessible is to ensure that everyone can fully and meaningfully participate in everything the college has to offer in the most integrative, inclusive and independent way possible,” says Erin Brown, director of the Disability Services Center. Yet ensuring the same opportunity to participate for all is more complex than one might think – and barriers to doing so often remain invisible to those unaffected by them.

For instance, educational maps that use red and green for emphasis are lost on students with color blindness because they can’t see the difference between these colors.

Snow removal plans that don’t prioritize building entrances with ramps and door buttons can leave students in wheelchairs out in the cold.

For a student with allergies to nuts or gluten, access to food becomes a barrier. Religious dietary practices like halal and kosher or ethical ones like veganism also impact access to food on campus.

According to Arthur Patrie, director of dining and retail food services, simply providing more and better options can make a real impact in a student’s day. “These include but are not limited to individualized counseling, menu support services and special menus, as required,” he explains. “Every day we have a variety of vegan and meatless options posted and available.” He notes that Donovan does not yet offer kosher food, but many of their snacks and prepackaged items are halal certified.

Other modifications have been made throughout campus to create a more welcoming environment and to encourage success for everyone.

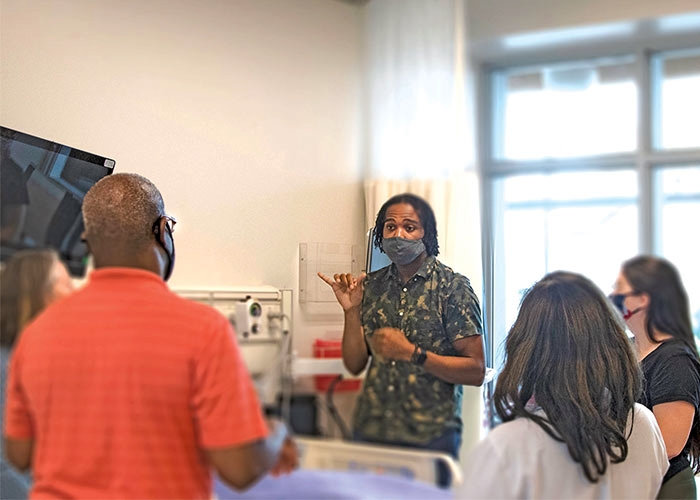

Braille, large print or audiobooks are examples of accommodations for people who are blind or who have visual limitations. For people who are deaf or have difficulty hearing, accommodations are made for an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter. But even requesting an interpreter can require a more thoughtful approach than it would appear at first glance. For instance, a deaf student in a master’s degree program may need not just an ASL interpreter, but one with a sufficient understanding of the course material in order to properly relay it to the student.

RIC’s Accessibility Committee works to ensure that the wide range of accessibility needs on campus are addressed. Recently, PressBooks was implemented, an open-source platform for creating, adapting and sharing educational materials to ensure documents are easily available in multiple formats. PressBooks benefit visually impaired students who use screen readers because PDFs, a common format for educational materials, are not screen reader-friendly.

Often accommodations benefit multiple demographics.

Captioned videos aid the deaf and hard of hearing, but they also make the videos in question more accessible to English language learners and those with old, failing devices. Single-use bathrooms aid people who use wheelchairs, but they also benefit queer spectrum individuals who may not feel safe or comfortable using gendered bathrooms.

Yet a person’s accommodation needs aren’t always so readily apparent. “There are studies that show that almost half of all veterans return with some kind of service-related disability,” shares Lisa Levasseur, assistant director of veterans affairs at RIC. “These students need substantial support in order to ensure equal access within their educational environment and to feel involved and engaged in the pursuit of higher education and the campus community.” For instance, a veteran who experiences PTSD may need to leave the classroom unexpectedly or require certain seating accommodations.

The Military Resource Center is working with the Disability Services Center to create a liaison between the two offices to ensure that these students are able to seek and receive the academic accommodations and resources they need.

Neurodivergent students, such as those with ADHD and autism, also have needs that are not apparent to most people. For instance, a student with ADHD may find it challenging to use standard organizational strategies often suggested by neurotypicals.

“The student who appears to be a procrastinator or unorganized probably already tried those organizational strategies too many times and has been unsuccessful in implementing them,” says Soumyadeep Mukherjee, assistant professor and co-chair of the Diversity Committee for the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development.

These students may experience frustration and feel discouraged when they can’t successfully implement these skills to make school more manageable, he says. It’s important for educators to recognize and try to assist students for whom neurotypical strategies do not work. As a bonus, providing flexibility in the classroom through take-home, open-book quizzes and flexible deadlines not only aids neurodivergent students but all students.

“The pandemic made me realize that it’s possible to allow untimed, take-home, open-Internet quizzes,” Mukherjee says. “As a result, many students no longer need to request special permission or accommodations. Similarly, recorded lectures for asynchronous viewing can help everyone.”

At RIC, campus-wide trainings are offered to bring greater awareness to unaddressed needs. Most recently, under Levasseur, Green Zone Training is being offered, which educates members of the RIC community on how to better recognize the needs of and assist military students.

Accessibility not only benefits students but also serves the interests of the institution. Providing all students with the same level of access is legally mandatory and key for colleges to achieve their retention and degree-completion goals.

“Higher education research shows that students who stay enrolled until degree completion is linked to a sense of belonging,” says Joise Garzon, director of Learning for Life, an office that links students to resources on and off campus to overcome obstacles to graduation.

“Accessibility to me is being intentional about ensuring that all are welcome and that folks find themselves fully engaged, no matter the setting or activity,” says Anna Cano-Morales, M.S.W. ’99, interim vice president of external relations and diversity, equity and inclusion. “It’s about feeling like you belong and working to include those that society has historically left out or weren’t mindful of.”

“My office oversees compliance and leadership to ensure that we’re all doing everything that is expected of us as a public institution,” she continues. “We work to make sure that the divisions are doing their part of the accessibility work. We also ensure that our state and federal mandates are being upheld within our programs and services. We offer a process to file a complaint if an individual feels that they have been discriminated against or harmed.”

Tangible institutional changes to make the RIC campus more welcoming and supportive for all are crucial, but Cano-Morales notes that individuals can act as well.

“Everybody can do their part to ensure that we promote accessibility and that we are more inclusive,” she says. “If we all asked ourselves, ‘Who are we leaving behind?,’ we would start a culture of all and not just of some.”

Whether the changes are institutional or individual, it takes many acts, small and large, to create a future in which everyone has access to everything that the campus has to offer.

“Accessibility is the welcome mat at the front door of a house. It’s the difference between a house and a home,” says Cano-Morales. “We all want to feel at home at Rhode Island College.”