Close Relations: Bio Lab Research at RIC

- News & Events

- News

- Close Relations: Bio Lab Research at RIC

If you work in a lab long enough, a lot of strange things start to look human.

Rhode Island College sophomore Raquel Villot has been working in the lab of geneticist and Associate Professor of Biology Geoff Stilwell for the past two semesters. The charmingly quirky sophomore disclosed that the first thing she does upon entering the lab is check on her children – fruit flies – the lab’s model organism.

“We’re always looking at them under the microscope,” she says, with a deeply dimpled smile, “and the more you look at them, the cuter they get. They’re like my kids.”

Villot’s brood is kept in what looks like an old fridge. It’s actually an incubator, with the temperature kept at a warm 73 degrees Fahrenheit. She pulls open the heavy steel door and a fruit fly escapes, along with the musty odor of a fridge that has sat unplugged for too long. Villot takes a look inside. There are thousands of them.

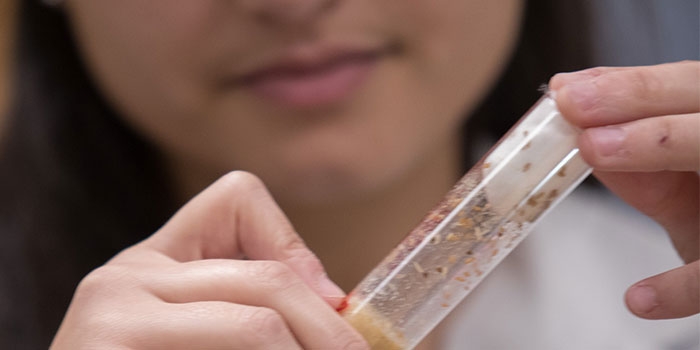

The flies are kept in corked vials arranged in rows on trays. Some of them cling to the glass walls of their cloisters; others seem to shiver, suspended in midair; while others feed on a mixture of corn meal, dry yeast, sucrose and agar at the bottom of their vials.

The lab depends on these insects to run their experiments. Stilwell is studying the effects of a mutant protein in brain cells that lead to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. One well-known sufferer was the late Stephen Hawking.

Although there are many different causes of ALS, scientists have identified one mutant protein called superoxide dismutase (SOD). Healthy SOD proteins protect the brain cells from toxins and other free radicals. Meaning, when a toxin enters the brain and attaches to a cell, SOD clamps onto the toxin to keep it from hurting the cell. However, mutant SODs fail to protect the cell, causing the cell to die over time and leads to paralysis, as in the case of Hawking.

Stilwell’s lab introduces the human mutant SOD gene into fruit flies, a common model organism in bio labs because they share many human genes, including 75 percent of those that cause disease. There are also an endless supply of them to experiment with. One female fruit fly can lay as many as 500 eggs in her brief lifespan. Their 40- to 50-day lifespan allows geneticists to study the fly’s complete life cycle.

Though the lab seems to have a bazillion of them, Villot is concerned about keeping the fruit flies alive.

“We don’t want the lines to die,” she explains. “Many have been bred to carry the ALS mutant. We’ve been having problems with contamination lately, like mold buildup and bacterial infections. I just want to make sure I have enough flies so that if a vial becomes contaminated I can toss it and it won’t affect my experiment.”

Villot and her lab mates crossbreed one set of flies carrying the ALS mutant with another set that is clear of the mutant. When the two sets mate, their offspring inevitably carry the mutant, Villot says.

“I take the offspring with the ALS mutant and heat shock them to activate their immune system. Then I heat shock them every other day and observe what happens,” she says.

Heat shock is a form of protein stress. Mutant SOD proteins will fail to protect the cells under protein stress. Villot wants to see what phenotype comes about as a result.

“A phenotype,” she explains, in her chatty, relaxed style, “is an expression of a gene. For example, the color of your eyes is a phenotype. Dimples are a phenotype. I’m looking for any kind of phenotype – shortened lifespan, paralysis, etcetera.”

Under a very sophisticated laser scanning microscope, Villot will be able to capture and analyze 3-D images of the flies’ brains. But today she will be applying the heat shock treatment. She’ll gather the flies into an empty vial, place them in a water bath that’s been heated to about 90 degrees Fahrenheit and let the vial sit in the bath for about an hour.

Villot says she loves being a part of scientific research. “You build close relationships with your lab mates and your professor,” she says. “Dr. Stilwell is very much a mentor figure. In fact, I find all of the biology professors friendly and approachable. They want you to succeed so they set you up to succeed.”

RIC’s Department of Biology offers numerous opportunities for laboratory research, led by experts in their field like Stilwell. Students benefit from experiential learning, they gain advanced-level lab skills that give them an edge when applying to grad school or med school and they gain invaluable communication skills in reviewing, writing and presenting their research findings at science conferences.

Click on Part 1, Part 3, Part 4 and Part 5 of this research series.