Segregation is Back in America’s Public Schools

- News & Events

- News

- Segregation is Back in America’s Public Schools

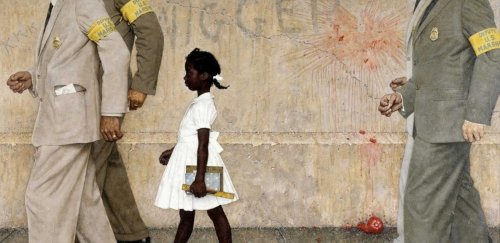

On November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated the William Frantz Public School. In retaliation, white parents withdrew their children and Bridges’s father was fired from his job. Ruby completed the first grade alone. Ruby’s walk to school the first day, escorted by U.S. Marshals, inspired the 1964 Norman Rockwell painting “The Problem We All Live With.”

“Segregation is like the elephant in the china shop. No one wants to admit it’s there,” said Jonathan Kozol, award-winning writer, educator and activist. “Yet America’s public schools are more segregated today than they were when Dr. King was assassinated in 1968.”

In a lecture on Oct. 21, Kozol spoke to a full house in Roberts auditorium. The facts he presented raised historical questions.

Didn’t the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 solve the problem of segregated schools? According to Kozol, “Yes and no.”

Although the 1954 Brown decision declared that separate schools for black and white children are inherently unequal, and although the achievement gap between black and white students narrowed between 1964 and 1970 when tens of thousands of public schools were integrated, by the 1990s a more conservative Supreme Court dismantled mandatory desegregation. And as early as 1991, segregated schools began to re-emerge throughout the country.

The average white student attends schools where more than 78 percent of the students are white; the average black student attends schools that are 30 percent white; and the average Latino student attends 28 percent white schools. Latino segregation is higher than black segregation in most regions, according to a 2003 report by the Civil Rights Project.

Kozol wore shirtsleeves rolled to the elbows and black tennis shoes. His lecture, like his appearance, was a mixture of cold, hard facts laced with black humor.

He described himself as a Jewish man who grew up in privilege in the suburbs of Newton, Mass. He graduated from Harvard a Rhodes Scholar but had never entered the nearby all-black community of Roxbury until he heard Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Kozol said it changed his life. Driving into Roxbury, he met with a black Episcopal priest (Dr. King’s representative) and asked how he could be of help to the Civil Rights Movement. The priest replied, “Our children don’t have enough teachers. Teach our children.”

Though Kozol lacked a teaching certificate, the Boston school department hired him as a substitute on a day-to-day pay basis. “There was such a shortage of teachers, they hired any warm body they found, no matter how inexperienced,” Kozol said. “The same hiring practice continues today.”

Kozol described the Roxbury school as a typical inner-city school, with a nightmare list of educational inequalities: a dilapidated and unsafe building; inadequate resources; less qualified, less experienced teachers; monstrous overcrowding; a limited curriculum taught at less challenging levels and a host of other factors that affect academic achievement.

Twelve different teachers had quit after only a few weeks or a few months, when he entered his fourth-grade class. The children were at a second-grade skill level in the winter of their fourth-grade year. There were not enough classrooms, so Kozol was forced to teach the 34 children in what he called “a horrible dilapidated auditorium” that he shared with another fourth grade and the glee club. The auditorium was in such disrepair that on one windy day a wall of rotted windows caved in on Kozol and his students.

“I grew up in privilege, so I know what it’s like in the rich schools,” Kozol said. “Their school districts spend twice as much per child, per year, in comparison to the inner city. These kids come to understand, sooner or later, that they aren’t valued by America.”

Throughout his lecture, Kozol made comparisons between inner-city schools and schools for the rich, the inference being, is it right that the origin of one’s birth should determine the quality of one’s education? Yet segregation is inextricably tied to class. Researchers have found that segregated schools are always positioned where poverty is concentrated.

“Children who are victims of class and race prejudice, the poor children of today, will become the poor adults of tomorrow, because our educational system ensures that they will be unable to compete with the better-educated children of the wealthy.”

— Jonathan Kozol

President Bush’s policy of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) is also “punishing” students in high-poverty minority schools, Kozol said. NCLB requires these students to meet specific test requirements in order to pass from one grade to the next.

“The average black or Latino 12th-grader reads and computes at the level of a 7th-grade white student. Roughly half of them won’t make it to 12th grade,” Kozol said.

“Bush essentially substituted test preparation for learning,” he went on. “Up to a quarter of the teacher’s school year is spent drilling students for tests to meet national standards.”

“And NCLB standards aren’t new,” he said. “The same standards were in use 40 years ago when I was teaching in Roxbury. They call for tightly timed school days with rigidly defined test-prep lessons.”

“Teachers are so afraid of deviating from these lessons that they discourage children from asking too many questions or engaging in in-class discussions. Principals are also in a state of terror. They’re told that if they don’t pop the test scores in their school by, say, four percentage points, they may become another headline: 'Near-Failing School,'” he said.

According to Kozol, the educational impact of a test-driven anxiety-ridden system of education means that the poorest children are being trained to think predictably and to parrot information they’ve learned by rote, while children of the privileged are being trained to think critically and to ask discerning questions. One group is learning to function with authority, and the other is being trained to regurgitate what they are told by those in authority, he said. In a democracy, this has huge ramifications.

“So long as these kinds of inequalities persist, all of us who are given expensive educations have to live with the knowledge that our victories are contaminated because the game has been rigged to our advantage.”

— Jonathan Kozol

If Kozol takes the nation to task for failing the children of the poor, he also uses humor as a leveling device to expose the absurdities of inner-city school life.

Kozol spoke before a full house at RIC.

Before the end of his first year in Roxbury, Kozol was fired for teaching a book by Langston Hughes. According to the school’s prescribed list of books, Hughes was for eighth-grade readers, not fourth-graders.

“When I was fired, I made headlines in the Boston Globe and the New York Times,” Kozol said. “It was an odd story. The headline read: Rhodes Scholar Fired from Fourth Grade. The formal charge against me: curriculum deviation.”

Kozol ended his lecture by making mention of his latest book, “Letters to a Young Teacher,” in which he writes a series of 16 letters to a first-year inner-city school teacher in Boston named Francesca. Francesca, he said, is one of many teachers on the front line who has refused to teach test-prep lessons, who has engaged her students in critical thinking and lively discussion and who has seen their achievement level grow. Kozol extended an invitation to the student-teachers in RIC’s audience to serve the children of the poor. He didn’t have to say it. They knew. “These children need you.”

Kozol has examined issues surrounding the public school system and inner-city conditions for most of his career. He graduated from Harvard University summa cum laude in 1958 with a degree in English literature and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford. He became actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement, and after teaching for several more years, he dedicated his time to writing. He is author of "Letters to a Young Teacher," "The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America," "Amazing Grace," "Savage Inequalities," "Death at an Early Age," "Ordinary Resurrections," "Rachel and Her Children" and "Illiterate America."

Kozol is also a recipient of the National Book Award in Science, Philosophy, and Religion (1968); the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award (1989); the Conscience-in-Media Award of the American Society of Journalists and Authors (1989); the New England Book Award (1992) and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award (1996), an honor previously granted to the works of Langston Hughes and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.